Welcome back to Meet the Magicians. In the second interview of the series I speak to Bert van der Wolf, founder and owner of The Spirit of Turtle. We discussed his life, his music, and of course DSD.

Step behind the curtain with me,

to Meet the Magician.

Bert van der Wolf has not only been around DSD since it’s creation, but was directly involved with it. His background in music and electrical engineering proved to be an extremely beneficial combination for him. Bert takes us through his experience as a technician, gear pioneer, and professional audio engineer and music producer. He shares about starting his own label Turtle Records and how he started working in the professional music world at Channel Classics,

which is where our conversation begins…

[Find Bert’s 3 Desert Island Albums at the end of the interview.]

How did you initially get involved with Channel Classics?

It’s a funny story actually. I was studying at the conservatory in den Hague and a guy from the school mentioned, “Hey there’s this studio in Amsterdam, they’re a bit busy so they need people”. So I went there one day and it was great, and I thought ‘Okay, this is it. I want to be here’ and Jared Sacks, the owner of Channel Classics gave the typical “Sure, I’ll call you”. I knew what that usually meant, so the next day I decided to drive there again. I still remember that day, probably the most important day of my life in the end, and I remember Jared opening the door with surprise and saying “What are you doing here? You were here yesterday!” I said ‘Yes, that’s true, but you have work so I thought I’d come by and see if I can do anything’. I don’t know what got into me to just go again, but I did. I went for a second interview with no appointment. And I’m so happy I did! But yeah, then Jared invited me in for a coffee and he showed me around a bit. I don’t remember why exactly because it was so long ago but for some reason I stayed all day, and the next day again for the third day in a row I went back. So that’s how it started. I began doing a bit of work there when suddenly Jared had a tragedy in the family and he had to leave for America. There was a giant stack of work on the desk that needed to get done and I just told him, ‘Hey, I’ll do my best. You can go and I’ll see what I can do.’

What kind of work were you doing there?

Well back when I first started there we did a lot of mastering and CD production for other labels actually. That is where the business was, the label wasn’t even there. Jared had a few recordings lying around with Frans Brüggen and Walter van Hauwe and some others that he had recorded, but that was not released and he was trying to plan that.

But mostly it was mastering and CD production?

Yeah it was. Those were amazing times. We did something like ten to fifteen masters a day and that was for the real money. But at the end of that year Jared wanted to start the label. And it’s an amazing story because for some reason I fell with my nose in the butter. [Dutch expression meaning: when you enter somewhere at exactly the right moment to have a certain benefit]. Unfortunately Jared got injured and had to stay in bed, and that was during the first recording, so I had to do it. And that was the first recording of the label, it was “Winterreise” from Max van Egmond & Jos van Immerseel.

Unfortunately this recording is not available in DSD format.

And that’s how it went, it just took off from there. It felt like an eternity of course, because we did SO many things in the beginning, it was something like forty productions in a year.

Wow, that’s crazy. Were you one of the only companies in the city that was offering this type of recording? I mean, that’s just so busy!

Well the thing is that I think we had a sort of monopoly on the digital editing and the mastering tools, because that was very expensive. Adriaan Verstijnen, who was my teacher at the conservatory and a great producer, he did his own stuff and often other labels from around the Netherlands would go to his place in Breukelen to do their editing because there was no other way to do it! But Jared already had the gear to do this, so we picked up a lot of work from the other labels around. So I think that was the reason we were so popular.

I see. Sounds like a busy time. So how do we get from working for Channel Classics to where we are now, sitting in your beautiful private studio?

It was, it was a busy time indeed. But at some point Jared wanted to move out of Amsterdam to Herwijnen and he asked if anyone from the company will go that way as well and I said that I would. I was actually the only one that wanted to. So the rest of the operation stayed in Amsterdam. We came out this way and we rebuilt the garage of the house that he bought into an editing studio and we were working from there. At the same time I had bought a house in Haaften and began setting up a studio as well. It was a lot to manage because there was so much still going on in Amsterdam, but we were out here and we enjoyed the quieter lifestyle. Eventually due to some personality differences the company kind of started getting complicated, so I decided to leave and do independent work. It was hard because I had to really restart from nothing. I tried working with a few people at first but that didn’t work out, so I think it was in 2000 that I decided to go fully independent and work on my own. I started very quickly with my own label with what at that time felt like a very fresh angle. You see, we didn’t know anything about hi-end audio at that time. We were just professionals in the production world. But at that time I was contacted by Harry van Dalen from Rhapsody in Hilversum who was in the hi-end world. He did his own recordings of musicians just for fun, but he wanted to try recording in higher resolution. He called and asked if I can rent him an A/D convertor so I brought it there and I walked in the shop and thought, “Wow, this is cool. What is this?!” As I said, I didn’t know anything of the hi-end audio world, so I was just stunned. I mean they had cables for hundreds of thousands of euros and speakers like… speakers like these [points backwards to his Avalon professional mixing monitors]. Harry actually recognised me and had some recordings on hand that I had done at Channel Classics. It’s hard to explain what it felt like hearing my music for the first time in real hi-end, but it’s as if I had been looking through a dirty window and suddenly it was totally clean and I could see every detail of every image through the glass. It’s funny because a lot of the records I made for Channel sounded great. Others that I thought were great for years, suddenly when I listened to them through these systems I thought, “Oh god…”. So yeah, suddenly everything kind of cleared up and I could see finally what kind of records I wanted to make. So we got talking and went for dinner and right away we clicked and began talking about starting a label that would be totally specialised in getting it right from start to finish. So we just began doing recordings together and that was it.

Well it makes me wonder… do you think that part of the reason you really gravitated towards the hi-end world once you found it is because of your background in electrical engineering?

I think probably that has something to do with it. Because of my background I was always heavily involved in the system setups and building of gear. I mean I had been working with dCS (hi-end audio systems pioneers) since I was at Channel, and I was responsible for maintaining our relationship with them since we had been importing and using their gear since the late ‘80s. And when I left Channel and had to restart my career from the beginning dCS really saved me because they offered me a job. They were really amazing. And the most incredible thing about that for me was that they demanded, ‘Well there’s only one way that you can be of any use to us, and that is when you stay working as a producer/engineer.’ You see, I thought they just wanted me to work for them as an employee for the gear and maybe sales, which they did, but they also wanted me to continue producing. So they allowed me to kind of start over again, and I could not imagine a thing like that. But they were happy because somehow I managed to create traffic to the company. And I was also their guinea pig for almost 30 years. They would send me new products and ask me what I heard, how did I like it? They needed feedback because they were all mathematicians and electrical engineers.

Of course, so they needed someone with the professional ear.

Yes exactly, they needed some connection between music and what they were making. And that worked out quite well, we had a lot of fun. I was also their contact person on the ground, going around and making sales, which allowed me at that time to meet everyone in the industry! It was really a great thing for me. And what happened fairly quickly actually is that I was contacted through dCS by Samsung because they caught wind that Sony and Philips were going for SACD and hi resolution.

Aha, so here we come to DSD!

That’s right. See, Samsung and other companies in Asia were really in to DVD/A and that was limited to 24-bit/96kHz. They heard about Sony and Philips going for higher resolution and they knew that they needed to come out with something that opposes that with the same resolution, otherwise they would be thrashed by SACD. So they asked dCS, “Can you produce a prototype A/D convertor in 24-bit/192kHz?” And dCS said that of course they could, no problem. Internally their converters were already 5 times higher resolution than DSD itself. I mean they used to be a company making these convertors for fighter jets, and then the owner had a change of heart and decided to go in to audio instead, so their technology was just way beyond what was happening in the audio world. So that’s what dCS did, I think they made the prototype in two days and sent it to me. Samsung came over with some technical guys, and for the first time ever in history we recorded in 192kHz. It’s just so funny that it was in opposition of DSD! But I remember being at dinner with the guys from dCS at that time and I told them, “Okay look I know we are doing this, but you have to also hop on the train of DSD”. And they laughed! Haha, they thought ‘Why would we want to do DSD when it’s 1-bit, and we are doing 5-bits? It’s just silly.’ But I told them that they better do it because it’s all going that way, and it sounds really good.

But what made you so certain that things were definitely going the DSD way?

Just the push from Sony and Philips was tremendous. I mean it was ridiculous. And I was a small independent, and I couldn’t compete with that push so I told dCS, “Please, make a prototype DSD.” And that was also like, boom, finished two weeks later. But then I had a problem, because you needed a special workstation in order to use these convertors, and there was just nothing there. I looked, I went on the market and I looked for a while and just found nothing. So I found a company in Arnheim that built editing systems for film who were very big in Hollywood. I went to them and I created my own DSD recorder. So I had the recorder and I was using the prototypes that dCS had created in 192 and in DSD, and no one at the time had those! It was really special and funny actually… I remember being at the AES (Audio Engineering Society) Convention in Amsterdam as an employee of dCS and I had brought and set up this whole system. I was showing people how I could record in DSD and suddenly some guys from Philips were at my back watching and asking, “Can you please explain what you’re doing here?” Haha! So within a couple of months I had an order from Philips to build three of these big systems for them, so I did. And they flew these systems around the world to make as many DSD recordings as possible, and they really went everywhere, but I had built them! It’s so funny, I still have the original manuals that I had written by hand.

Wow, that is amazing. Your involvement in the creation of DSD as a whole is impressive. If I look at what you’ve done in your career up until now it makes me curious about your childhood. Did you grow up thinking you wanted to have a career in music?

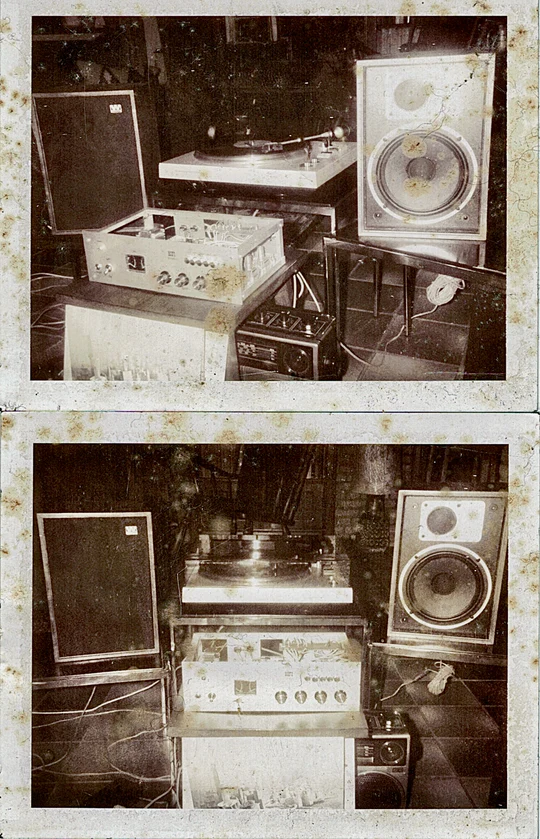

Yes I did. My sister was a piano teacher and I started on the piano very young, I think around the age of seven and I trained until I was thirteen or so. Then I discovered the classical guitar and I loved that. Turns out I was a little bit above average at that, probably because I had already trained the piano for a while, so the teacher recognised that and I was sort of his ‘prodigy’ and he was gearing me up for the conservatory. But I also played in bands and was doing pop music and stuff. Yeah, music was my life. But then my father kind of… disagreed, as most fathers did about music in that day. He felt I should do something that would make some money. So that was, um, a bit more than a gentle push toward studying electronics. Because I had two hobbies, one was music and the other was electronics. Actually, this all started with this… [Bert walks across the studio and brings over an old polaroid photo of a speaker system he had built as a child]

So I was in to electronics and I started with two old mis-match tube radios, a stereo record player, and amplifiers that I had built myself. I listened to old vinyls that my parents had and that’s when it started for me, the magic of sound and acoustic audio. So it was a logical choice to do electrical engineering after school which I did for three years and it was horrible, I hated it. And I felt really strongly, ‘how am I going to get music in my life again’? So I applied to Polygram in Baarn but they said that they only take people from the dedicated recording engineer/producer schools.

Oh tough timing that they were only taking people from there. I’m sure that just before that time those kinds of schools didn’t even exist?

No! They all had guys, electrical engineers like me, to be the technicians at recording sessions and they partnered with the producers, who were all musicians who didn’t make it or something. But now Polygram was only hiring people from those schools. So I tried going back to finish the electrical course, but I was told I would need to do a six month internship at the railway and I thought, “Nope! No way am I doing that.” So I quit. I had to go in the army for a year and that was awful. And then after that I started the recording engineer course at the conservatory and it was just instant. Everything went so smooth after that and after a couple years in that course I got the internship at Channel Classics, then shortly after began working with dCS and the rest is history. Nothing was in my way really, it just all happened at the right time.

My final thoughts…

Well it sounded like Bert ‘fell with his nose in the butter’ many times throughout his life, and I’m very glad that he did. It was fascinating to learn his story in music and especially with DSD. What an honor it was, to sit with someone who played such an integral role in how music is recorded in DSD. A big thank you to Bert van der Wolf for sharing a bit of his magic with us.

This was surely an interview that I will not forgot.

Bert’s 3 Desert Island Albums

-

Prokofiev Symphonies Nos. 1 and 5€20,99 – €28,49

-

Think… It’s All Good€16,99 – €20,99

-

Concerti Grossi Op. 6 [Triple Album]€28,99 – €39,49

![Concerti Grossi Op. 6 [Triple Album]](https://media.cdnb.nativedsd.com/storage/nativedsd.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/01061016/CC72570-No-Logo.jpg)