Welcome to the first edition of ‘Meet the Magicians’, an interview series where I take you into the rooms with engineers, producers, musicians, and anyone else who is involved in making the magic of music come to life!

I spoke with Tom Peeters – founder, owner and producer at Cobra Records. It was a pleasure to spend a couple hours in Toms studio getting to know him. He may be a calm man on the outside, but from speaking to him about music you can feel that inside he is bursting with enthusiasm and passion for his craft. From growing up in the Jazz scene in the Netherlands, to wanting to become a teacher and eventually giving that up to pursue a career in music, Tom’s story was an exciting one to hear. At the end of the interview Tom gives his ‘NativeDSD Desert Island Picks’ – 3 albums that he could not live without if stranded on an island. So without further adieu, please enjoy Tom Peeters.

Well Tom, since we are here to talk about your history with DSD, I figured we could jump right in. How do you remember first learning of DSD?

In the ‘90s I was working at Channel Classics, but it wasn’t until after I left that I started hearing about DSD. I was no longer working for them but was still in contact with Jared Sacks, and they started to record in DSD I believe in the early 2000s somewhere. Philips was developing this equipment and Channel Classics was approached by them to use it and to help bring it in to the market. So I heard about it at that time from Jared. Then some years later Philips and Sony decided to stop the manufacture and development of DSD equipment because the market was not big enough for it. That’s when Channel Classics did something quite important and historically significant. They decided to sell digital versions of the master copies of albums. Basically, up until that point the way it worked was that you created the master tape of an album, and what you sold were copies of that master, which always reduced in quality through the process. Instead of doing that, Channel Classics decided to sell the masters in DSD format, so that everyone had the chance to hear the original quality and original print of an album. We don’t really think about it now because so many labels do the same thing, but at that time it was an important moment.

And when did you begin recording in DSD?

Around 2007 I remember Philips was stopping their production of DSD equipment in Eindhoven, and at that time I was able to purchase from them the gear that was necessary to record in DSD. The funny thing is that I never released or sold anything in DSD until many years later. See, back then in 2007 there was still no digital distribution of DSD music. The only way this music was being sold and consumed was on SACD (Super Audio CD), but I had no interest in producing those because it was not financially attractive. Still, I recorded my projects in DSD. It was only many years later that I began selling those albums in DSD, and that is because NativeDSD had started and there was suddenly a platform where you could sell digital DSD music. I was actually one of the first labels to distribute music on NativeDSD.

Do you remember the positive and/or negative sides of recording in DSD when you first began?

Without question the biggest benefit was the quality of sound. It was just so much better than anything we were doing and making into CDs at the time. A world apart. One challenge I remember was the number of available tracks. When I began recording in the early ‘90s you only had two channels. We would sometimes be recording a large orchestra and be using 24 microphones that we would have to mix ‘on the fly’ to two channels. Then as the years went on and new technology came out, we had more and more channels to record to, until eventually the number of channels was limitless (or at least limited to the number of physical inputs we had). But when I began recording in DSD I was suddenly limited to eight channels. Not only that, but the standard practice when recording in DSD was to also record in 5-Channel Surround Sound, which meant I had to use five channels for that, leaving me with only three for spot microphones. So I had to return to my roots and use a large analog mixer in order to use more microphones.

When and how did you start Cobra Records?

In 2001 I began my company Mediatrack with two partners when we took over the facilities that Channel Classics used to own. They were a production facility as well as a label, and around that time in 2001 the label had grown enough to stand on its own, so my partners and I took over the facilities. We produced CDs for clients of all types as well as offered booklet design and the physical manufacture of the CDs. The other big part of the company was mastering. We had two mastering suites in Amsterdam often working six or seven days a week in shifts, continuously making masters. We also had the production part of the company where we focused on recording and producing classical music.

And is that where your focus always was? On being in the studio and creating records?

Sure, during my career that has been true, but I actually went to school at the conservatory in Den Hague to become a music teacher. I had always thought that I really wanted to teach music in schools because the way that music affected me was something I though everyone deserved to experience. As I was learning to become a music teacher I saw that the conservatory also offered a class in recording, now called the Art of Sound. I decided I really wanted to follow that course as well because working with recording equipment had been a hobby of mine growing up. I quickly realised that it was more than a hobby for me now, and that I had a real interest in pursuing this as a career. After a long year of teaching music full-time and attending the Art of Sound course I had to make a tough decision, and I left my job and pursued audio engineering as a career.

Was that a very hard decision for you to make?

It was not very hard, no. I had so much passion and interest for recording that it felt right. Also, as a recording engineer – well, mostly as a producer – I felt that my teaching skills came to good use. During the session I am constantly coaching and instructing players how they can evoke the emotion they are trying to find. I am still teaching, sometimes.

How was the music seed first planted in your life? Did you grow up in a musical home or did you take lessons as a child?

Well I think it was definitely my home. When I grew up there was always a lot of music. My father played piano, all of his brothers were always making music, and his youngest brother was quite a famous jazz musician. As a young boy I would often go to his gigs and help him by carrying his instruments, so I really grew up around the jazz scene. The same uncle actually taught me to play the piano. I never really thought to make music a career though. Only years later when I was in high school did I have experiences in bands and with musical performances which made me think: ‘Wow, these musical moments are so fun and they go so deep… everyone should be able to experience this. It should not matter whether or not you are going to be a professional, everyone should know what this feels like.’ That is when I thought I would like to become a music teacher.

It seems you are very emotionally connected to music and have been since those first experiences in high school. This makes me think of Cobra Records’ goal, that ‘Every Cobra album is a storytelling project’. How does a mission like that come to be?

It grows. Yeah, it really grows. Now it’s easy for me to look back and see that I was always most interested in these projects, even in the beginning of my career. These were the most joyful projects for me, when I found these stories. Nowadays there are more and more really talented musicians. The technical ability is going up and up, and it seems everyone can play the main repertoire perfectly. So the question then becomes: ‘Well why should you play it, and how can you make a difference?’ And in the end, that’s the story. And I am drawn to the musicians who find it necessary to tell their story, to explain their message, and to share their experience. This is something I often see is helpful for the artist too, because their story is their brand. Cobra is not the brand, the stories are brands.

Running a label in that way must draw in some really amazing artists to work with.

I think it does yes. But you know, I never really wanted to run a label. I actually started Cobra with the goal of it being more of a community than a label.

What does that mean exactly, a community?

Well before I started Cobra I was just a recording engineer for hire, and through that work I started to notice many artists who had really amazing stories. The only problem was that back then to make an album they had to either be picked up by a label, or have a lot of money to pay someone to make it for you. That’s when I thought to start Cobra, a label – but not really. Somewhere you could come to make an album if you didn’t have too much money. Somewhere that is focused on the emotion and the story. That’s why we operate under a fair trade system which means the artist pays what they can to make an album, but Cobra Records also pays. That way we both have invested interest in the album succeeding.

Can I ask, how did you decide on the name Cobra Records?

Yeah, of course. Well obviously it’s a snake. Haha. And I wanted to have a label that could move like a snake with the industry, easily adapting and changing direction. But mostly it comes from the painters initiative called CoBrA (Copenhagen, Brussels, Amsterdam) which was a group of painters in mid 20th century who found each other and really did something different. They really challenged the ‘norm’ and wanted to do things in a very different way than what was expected. And before I started Cobra Records I saw a lot of things in the music business world that I wanted to stay away from. I even remember thinking, ‘I never want to own my own label. No way.’ But then I saw all of this music around me that I thought the world really needed to hear, so I started Cobra Records with the same mission as the original painters initiative – to do things differently than how they are done right now.

Lastly I’d like to get your ‘Desert Island DSD Picks’. Two or three a few of your favourite DSD albums to listen to.

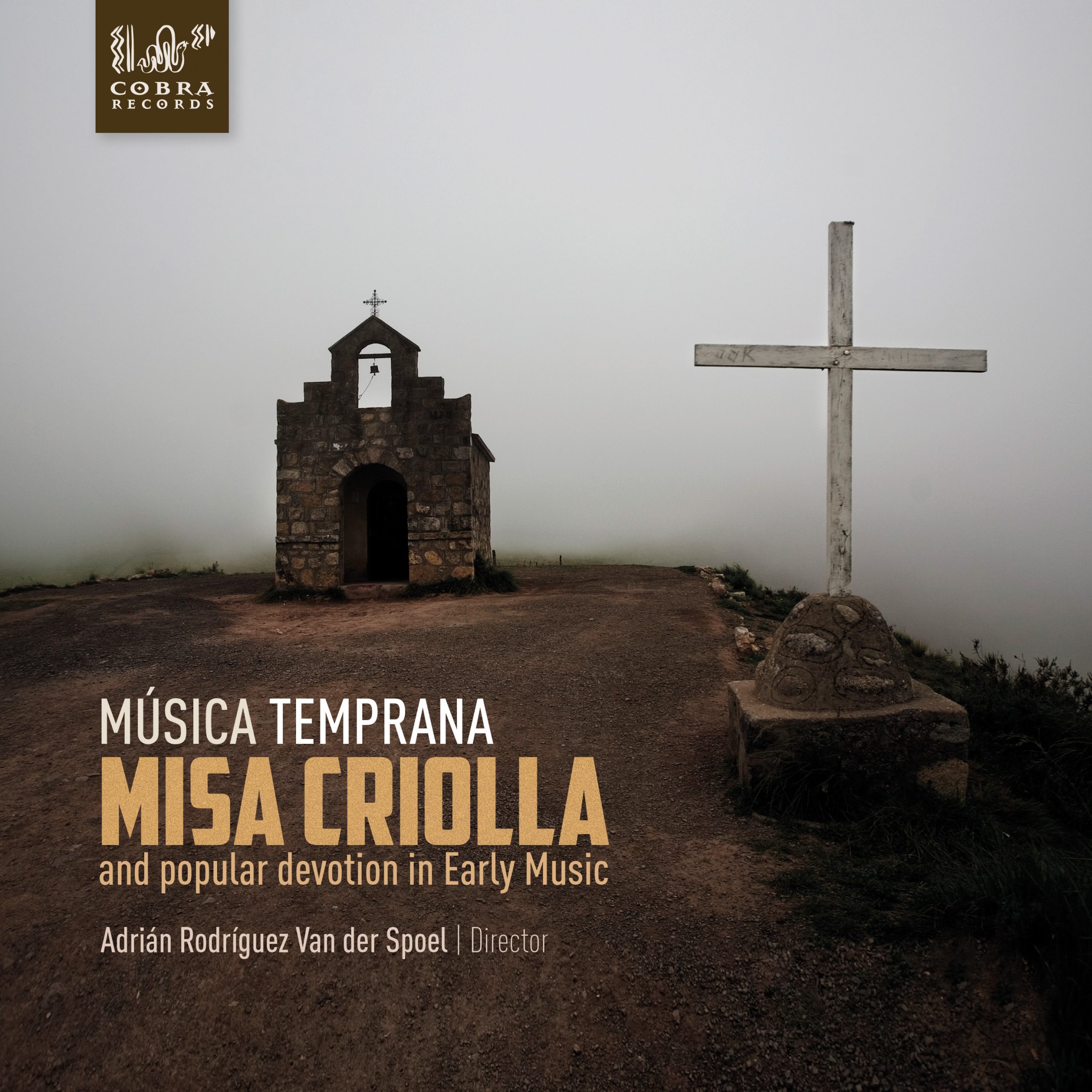

Oh that is a tough on. Let’s see… One I would have to include is called “Misa Criolla”. On there is a track with only three singers and one viola da gamba (a sort of cello) and somehow that is always kind of a heavenly song for me. Another would be “Frei Uber Einsam” performed by the Cuarteto Quiroga. I always thought I didn’t like Brahms, he was a very difficult composer, a difficult personality and really struggling in his life. I always felt his music very heavy to listen to. Finally I discovered that some people can play it and just let the music do everything and not work on it too much. This quartet was one of them, and they really helped me enjoy and hear Brahms work in a different way. The last album I would include is called “Solo” by Nuala McKenna. The attention she holds with just the cello is remarkable and I am always pleasantly surprised with the passion she brings to her performances.

Tom’s 3 Must-Have Desert Island DSD Albums

-

Misa Criolla€16,99 – €30,99

Misa Criolla€16,99 – €30,99

-

Frei Aber Einsam (Free But Lonely)€15,99 – €36,99

Frei Aber Einsam (Free But Lonely)€15,99 – €36,99

-

Solo: Kodaly, Ligeti, Britten€18,99 – €37,99

Solo: Kodaly, Ligeti, Britten€18,99 – €37,99